Old Billy, the oldest horse ever recorded 1760 – 1822. Edmund L. Seyd

Old Billy, the oldest horse ever recorded 1760 – 1822. Edmund L. Seyd

While old Billy never worked on the New Cut Canal he had strong associations with the original waterways of the Irwell and Mersey. He had just retired as the New Cut Canal was opened on 14 February 1821.

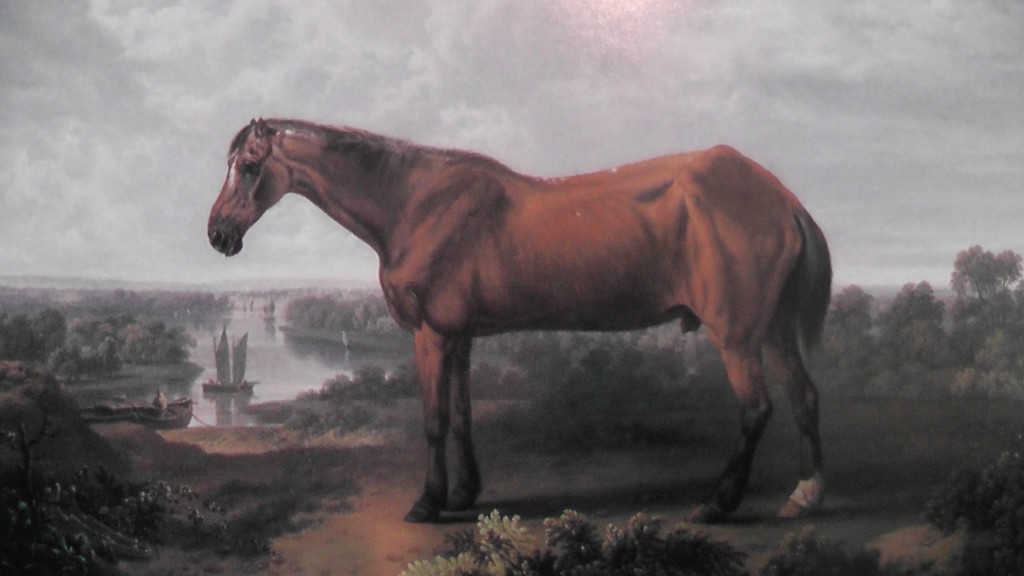

Thanks to Warrington Museum we have been given permission to use this image known as the Towne painting and the following excerpt from their records.

Reprinted from the Museums Journal Volume 73, Number 4, March 1974

‘Old Billy’ is frequently the subject of letters in the correspondence columns of The Field or Country Life and on several occasions his name has found its way into The Times and Manchester Guardian. The fascination that Old Billy continues to exert is that no other horse has yet wrested the record for longevity from him. He was born in 1760 and had lived to the ripe old age of 62 when he died in 1822. The life span of the only surviving species of wild horse, Equus przewalskii, is between twenty-five and thirty years and the average age at which the domestic horse dies or is destroyed is much the same, between twenty and twenty-five years. However, there are some records of horses which have lived on into their thirties, forties, and even fifties, though their authenticity is very difficult to determine. Not only did Old Billy outlive them all but his longevity is fully authenticated. Moreover his life-story has many museum and art gallery connexions, as well as local historical interest.

Almost the whole of Old Billy’s life was spent in the service of the Mersey and Irwell Navigation Company. Forty years before his birth the founders of the company had made these two rivers navigable between Warrington and Manchester by the construction of locks and cuts. Old Billy was bred by Mr Edward Robinson of Wild Grave farm in Woolston, a short distance from Warrington.

He was foaled in 1760 and in 1762 was trained to the plough by Henry Harrison. It seems probable that the Mersey and Irwell Navigation bought him in 1762 or 1763. He was employed as a gin horse and in towing boats until 1819, when he was retired to a farm on the estate of one of the directors of the company, William Earle of Everton. Here on the farm at Latchford, near Warrington, Old Billy lived out the last three years of his life in ease until he died on 27th November 1822. The evidence supporting these facts about the life of this remarkable animal comes from four main sources. First, the paintings of two nineteenth century artists, Charles Towne and William Bradley; second, reports in the press, particularly the Manchester Guardian; third, records of the Earle family, which has been closely associated with the Old Billy story from its inception; lastly, the fact that the skull and stuffed head of the old horse were preserved.

He was foaled in 1760 and in 1762 was trained to the plough by Henry Harrison. It seems probable that the Mersey and Irwell Navigation bought him in 1762 or 1763. He was employed as a gin horse and in towing boats until 1819, when he was retired to a farm on the estate of one of the directors of the company, William Earle of Everton. Here on the farm at Latchford, near Warrington, Old Billy lived out the last three years of his life in ease until he died on 27th November 1822. The evidence supporting these facts about the life of this remarkable animal comes from four main sources. First, the paintings of two nineteenth century artists, Charles Towne and William Bradley; second, reports in the press, particularly the Manchester Guardian; third, records of the Earle family, which has been closely associated with the Old Billy story from its inception; lastly, the fact that the skull and stuffed head of the old horse were preserved.

The Bradley painting The most important piece of evidence is the Bradley painting. William Bradley (1801 – 57) was Manchester-born but moved to London in 1822, the year of Old Billy’s death, to establish himself as a successful portrait painter. Although only twenty when he painted the horse in 1821, it is easy to understand how the commission came his way, for already by the age of sixteen he had begun to advertise himself as a ‘miniature and animal painter’.

The Bradley painting The most important piece of evidence is the Bradley painting. William Bradley (1801 – 57) was Manchester-born but moved to London in 1822, the year of Old Billy’s death, to establish himself as a successful portrait painter. Although only twenty when he painted the horse in 1821, it is easy to understand how the commission came his way, for already by the age of sixteen he had begun to advertise himself as a ‘miniature and animal painter’.

Beamont, in his A History of Latchford, says that it was the owners of the Mersey and Irwell Navigation who arranged for Bradley to paint Old Billy, after they had pensioned the horse off for life out of respect for his age and long service. There must have been considerable local interest in the horse, for subsequently the painting was engraved by Thomas Sutherland and a number of coloured lithographs were produced, some of which still exist in art galleries and museums. To add interest to these lithographs an account of Old Billy was printed below them, which reads as follows:

‘This print exhibiting the portrait of Old Billy is presented to the public on account of his extraordinary Age. Mr Henry Harrison of Manchester whose portrait is also introduced has nearly attained his Seventy Sixth year. He has known the said Horse Fifty Nine Years and upwards, having assisted in training him for the plough, at which time he supposes the Horse might be two years old. Old Billy is now playing at a farm at Latchford, near Warrington, and belongs to the Company of Proprietors of the Mersey and Irwell Navigation, in whose service he was employed as a Gin horse until May 1819. His eyes and teeth are yet very good, though the latter are remarkably indicative of extreme age’.

There is no mention in this account of the place where Old Billy was born, and in particular of the date of his death, but this same account appears on all the half-dozen lithographs I know to exist, one of which is in the Manchester City Art Gallery.

However, as a result of a correspondence in the Manchester Guardian in 1876, the missing information was supplied under the signature of ‘R. H.’ In a lithographic print that ‘R. H.’ had seen there was this addition to the account quoted above;

‘Certificate – Mr H. Harrison, of Young Street, Manchester, certifies that the horse belonged to the company of Proprietors of the Mersey and Irwell Navigation, known by the name of Old Billy, came to grass on Wild Grave Farm when he (Mr Harrison) was 17 years old, and that he is now in his 75th year of his age. Mr H. supposes that Old Billy was at that time two years old. Old Billy died November 27th 1882, in the 62nd year of his age’.

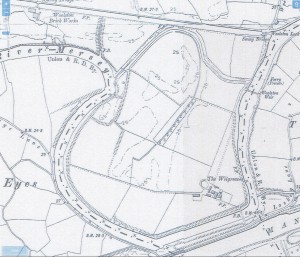

A study of the Bradley picture enables us to pinpoint more or less the place at which the artist was standing when he painted Old Billy and Mr Harrison. About a mile to the east of Warrington the Mersey makes a sharp loop; if you stand in this loop and look westward towards Warrington, you have the river in front of you and a church tower and a white building are visible as in the painting. The tower belongs to the parish church of St Elfin, founded in 670 A.D. and the oldest church in Lancashire. Today it has a very tall spire, but this was not added until 1859.

The white building is now* the Warrington Maternity Home but in 1821 it was known as the Old Warps House.(* written in 1974. The Old Warps House is now Spirit Restaurant) That the farm that Old Billy was retired occupied this area to the east of Warrington is confirmed by a contemporary account of a visit by a Mr Johnson to Old Billy, in which it is stated that the horse was at Latchford Lock. Latchford or Manor Lock lies at a point on the Mersey just before it takes a sharp bend described above, and is the opening of the old Latchford and Runcorn canal. Further confirmation comes from A History of Latchford, in which Beamont says that Old Billy was to be seen in the grounds of the Mersey and Irwell Navigation near the Old Warps House. Beamont adds an interesting note to the effect that the Company had put Old Billy in ‘special charge of one of their old servants, like the horse, also a pensioner for his long service, to look after him…….’ This old servant was none other than Henry Harrison, hence his presence alongside Old Billy in the Bradley painting.

The Towne painting

The Towne painting

The other artist associated with the name of Old Billy, Charles Towne (1763 – 1840), was an early member of the Liverpool School, and has been described as ‘a ‘’Little Master’’ who painted for a provincial public during the years of rapid industrial overthrow of a once rural environment……’ By the 1790’s he was becoming an experienced animal painter and receiving commissions from gentlemen for portraits of their favourite hunters. As one of Britain’s ‘sporting artists’ it is easy to understand why he should have been commissioned by William Earle, a director of the Mersey and Irwell Navigation, to paint Old Billy.

Towne’s visit to see Old Billy at the invitation of William Earle took place on 11th June 1822, in the company of a veterinary surgeon, Robert Lucas, and a Mr W. Johnson, who described the visit in a letter to Annals of Sporting. Unlike the Bradley painting, much of the landscape in Towne’s picture is probably imaginary, for he had a romantic approach to landscape, derived from de Loutherbourg and Morland, and some of his landscapes are imitations in the manner of the Dutch Italianate School of the seventeenth century. This painting has been handed down through the Earle family and is now in the possession of Colonel Charles Earle, William Earle’s great-great-grandson, who has bequeathed it to the Manchester Museum. A second Towne painting of the horse is held by the Williamson Art Gallery and Museum, Birkenhead, and two others are known to exist.

The written record

The most important press material relating to Old Billy is the letter from Mr Johnson to Annals of Sporting in 1822 (noted above) and a news item which appeared in the Manchester Guardian of Saturday, 4th January 1823, and which reads as follows:

‘Longivity of a Horse – A horse, the property of the Company of Proprietors of the Mersey and Irwell Navigation, was some time ago freed from further labour, and sent to graze away the remnant of his days. Wednesday se’nnight this faithful servant died, at an age which has seldom been recorded of a horse: he was in his 62nd year’.

The connexion between the Earle family and Old Billy has already been touched on, and the family records add further proof of the authenticity of the horse’s history.

William Earle of Everton (1760 – 1839) was a prosperous shipowner and merchant who owned considerable property in the Liverpool area. As a director of the Mersey and Irwell Navigation it was natural for him to offer a home to Old Billy on a farm on one of his estates when the company retired the horse. There is an entry (1904) in the diary of his great-grandson, Maxwell Earle, to the effect that Old Billy was allowed to graze away in William’s park and we know from Johnson’s letter to Annals of Sporting that William was present when Johnson, Towne and Lucas went to visit the horse.

The skull and head

Old Billy’s skull found its way into the collections of the Manchester Museum via those of the Manchester Society of Natural History. This Society was founded in 1821, so that the skull was one of the first exhibits in its premises in King Street. Ten years later the collections were moved to a larger building at the junction of Peter Street and Museum Street, and ‘Ulmus’, in answer to a query, was to write to the Manchester Guardian in 1876 to say that he always ‘thought that Old Billy appeared in skeleton form in the Museum in Peter Street and that his skin was not far off, both being under the stairs in that building’. By the 1860’s the society was experiencing serious financial difficulties and in 1878 it disbanded after handing over its collections to Owen’s College, later to become the Victoria University of Manchester. The College built the present Manchester Museum in 1888 to house the collections and it is here that Old Billy’s skull has been displayed for the last eighty-five years.

Old Billy’s skull found its way into the collections of the Manchester Museum via those of the Manchester Society of Natural History. This Society was founded in 1821, so that the skull was one of the first exhibits in its premises in King Street. Ten years later the collections were moved to a larger building at the junction of Peter Street and Museum Street, and ‘Ulmus’, in answer to a query, was to write to the Manchester Guardian in 1876 to say that he always ‘thought that Old Billy appeared in skeleton form in the Museum in Peter Street and that his skin was not far off, both being under the stairs in that building’. By the 1860’s the society was experiencing serious financial difficulties and in 1878 it disbanded after handing over its collections to Owen’s College, later to become the Victoria University of Manchester. The College built the present Manchester Museum in 1888 to house the collections and it is here that Old Billy’s skull has been displayed for the last eighty-five years.

There is, however, no record of the Manchester Museum ever having possessed the stuffed head of Old Billy, which is now in the Bedford Museum. Perhaps the Manchester Natural History Society, when it fell on hard times, sold the specimen. The head was presented in 1932 to the Bedford Modern School Museum (whose collections were later incorporated the Bedford Museum) by Mr Harry Peacock, a local auctioneer. The special feature of the skull is the extreme wear on some of the grinding teeth. William Earle’s son, Charles (1798 – 1881) told his grandsons, Lionel and Maxwell, that Old Billy died from malnutrition due to his molars having been ground down to the gums.

There is, however, no record of the Manchester Museum ever having possessed the stuffed head of Old Billy, which is now in the Bedford Museum. Perhaps the Manchester Natural History Society, when it fell on hard times, sold the specimen. The head was presented in 1932 to the Bedford Modern School Museum (whose collections were later incorporated the Bedford Museum) by Mr Harry Peacock, a local auctioneer. The special feature of the skull is the extreme wear on some of the grinding teeth. William Earle’s son, Charles (1798 – 1881) told his grandsons, Lionel and Maxwell, that Old Billy died from malnutrition due to his molars having been ground down to the gums.

Old Billy’s place in equine history is certainly assured, recorded as it is both in paint and in print. Among the items of news thought important enough for inclusion in the Annals of Manchester for the year 1822 are the laying of the foundation stone of the Town Hall, the trial of certain military gentlemen for their suspected part in the Peterloo Massacre, Shudehill. Sandwiched among these and other items is the following:

‘The death of ‘’Old Billy’’ excited a great deal of interest. ‘’Billy’’ was a horse belonging to the Mersey and Irwell Navigation, and when he died, 27th November, was in the 62nd year of his age’.

Acknowledgements

I wish to express my thanks to the members of staff of the museums, art galleries and libraries of Manchester, Salford, Warrington, Birkenhead and Bedford for providing me with information and historical material relating to Old Billy. I am particularly grateful to Mr G.A. Carter, Warrington Library, for giving up so much of his time to answering my many enquiries, and I owe a special debt of gratitude to Lt-Colonel Charles Earle of Blandford House, Sutton Montis, for allowing me to draw on his wide knowledge of the period and on the Earle family records.

More images and information can be found on this link to atlasobscura.com with thanks to Allison Meier for many of these images taken from her article.